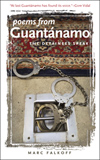

But there were poets writing about the conflict who were not impossibly remote, but held in a prison that is ostensibly US sovereign territory on a Caribbean island, poets whose rights and lives were scrutinised in detail by the press, and whose orange jumpsuits have become a visual shorthand in contemporary cinema, poets who do not fit our conventional image of war poets as noble combatants under sufferance. As they were written about, so many of those held at Guantánamo wrote: on polystyrene cups, with toothpaste, and later - as a humanitarian gift from the guards - with paper and pencils. Many of these poems were destroyed as a threat to US security, but some were smuggled out by human rights activists and lawyers, and collected in Poems from Guantánamo.

But there were poets writing about the conflict who were not impossibly remote, but held in a prison that is ostensibly US sovereign territory on a Caribbean island, poets whose rights and lives were scrutinised in detail by the press, and whose orange jumpsuits have become a visual shorthand in contemporary cinema, poets who do not fit our conventional image of war poets as noble combatants under sufferance. As they were written about, so many of those held at Guantánamo wrote: on polystyrene cups, with toothpaste, and later - as a humanitarian gift from the guards - with paper and pencils. Many of these poems were destroyed as a threat to US security, but some were smuggled out by human rights activists and lawyers, and collected in Poems from Guantánamo.In her most recent book Frames of War, Judith Butler takes up this collection to explore two questions (well, many interwoven questions, as ever in Butler's complex thought, but two that I want to tease out): what is it that poetry can do, or does, that might make it a threat to US security; and she finds the start of a response to a larger question ("what is the self?") in her answer. Poetry records both the injurability of the body in conditions of war and torture, and its ability to survive. On the surface, both of these might challenge 'official' narratives of Guantánamo by creating sympathy for prisoners, and by providing evidence of torture.

But looking deeper, Butler argues that these poems, recording injurability and survivability, attest to the interconnected social nature of the body and self in a way that complicates the frame of war, which demands, in her words, that some lives be rendered worth less than other lives, or even not lives at all, and therefore ungrievable. So poetry, because it is shaped around recording the affect of the writer and generating affect in the reader, can restore grievability to these devalued lives with maximum impact.

But looking deeper, Butler argues that these poems, recording injurability and survivability, attest to the interconnected social nature of the body and self in a way that complicates the frame of war, which demands, in her words, that some lives be rendered worth less than other lives, or even not lives at all, and therefore ungrievable. So poetry, because it is shaped around recording the affect of the writer and generating affect in the reader, can restore grievability to these devalued lives with maximum impact.But Butler also points to the nature of poems as written artefacts:

The words are carved in cups, written on paper, recorded onto a surface, in an effort to leave a mark, a trace, of a living being - a sign formed by the body, a sign that carries the life of the body. And even when what happens to a body is not survivable, the words survive to say as much. This is also poetry as evidence and as appeal, in which each word is finally meant for another. (Frames of War, 59)The materiality of these poems, their embodiment - she goes on to talk about the relationship between poetry and breath - make them part of the exchange that is the interdependence of self and other.

What Butler doesn't add is that there is a long and lasting tradition of poetry as a social art throughout the Arabic and Persian speaking worlds, of poetry as part of the weaving of community as it is performed at ceremonies and parties and in competitions. Poetry is "meant for another" in this sense as well: meant to connect backwards through references to the Qu'ran and even pre-Islamic poetry that still echoes in composition in Arabic today; and meant to connect forwards (or rather sideways, through the bars) to make a prison - an enforced atomisation - into a community where each self speaks with and answers to another, and thus each poet restores himself to grievable life, not by writing for himself, but for the others.

I think this note of cultural specificity, oriented to the shared poetics of the Qu'ran as a communal literary form, adds weight to Butler's reading of how the

poems communicate another sense of solidarity, of interconnected lives that carry on each others' words, suffer each others' tears, and form networks that pose an incendiary risk not only to national security, but to the form of global sovereignty championed by the US… As a network of transitive affects, the poems - their writing and their dissemination - are critical acts of resistance, insurgent interpretations, incendiary acts. (Frames of War, 62)

No comments:

Post a Comment