In the thirteen years since Judith Butler published Antigone's Claim (having first performed the book as a series of Wellbeck Lectures), the question of what Antigone is claiming – as a woman, and in the aftermath of war – have become ever more pressing. In retrospect, the book seems uncannily prescient of the questions of grievability and vulnerability raised by the events of 9/11 and subsequent imperial wars, as addressed by Butler in her recent work. Both The Watch by Joydeep Roy-Bhattacharya and The Patience Stone by Atiq Rahimi draw on Antigone (the former more explicitly than the latter) for Afghanistan-set stories of female mourning outside the law.

Moira Buffini's play Welcome to Thebes resituated Sophocles' play in that mythical unnamed country, Africa; making surface reference to (and drawing a charge from association with) the revisioning of tragedy practised by Wole Soyinka, Sarah Kane and Yael Farber, Buffini's conventional drama - like Roy-Bhattacharya's and Rahimi's novels - relies, as an update and relocation, on a creepy, tired notion of ontogeny recapitulating phylogeny -- that is, on a EuroWestern sense that contemporary Afghanistan or "Africa" are culturally analogical to ancient (mythic) Greece. These over-theres are cast as primitive, embroiled in the awful, terrible beholden-ness to gods and fate from which our supposed civilisation has supposedly rescued us. It's a melodrama composed out of pity porn, made august by its claim to the classics.

Of course, Greek tragedies are endlessly rewritten and updated, and the century after Freud's Oedipus has proved particularly fruitful for the Theban cycle. Butler recommends Antigone as a post-oedipal position from which to rethink psychoanalysis and ideas of both identity and identification, for example. Rather than outsideoverthere, Butler puts Antigone in us: not as an archaising exercise, but out of frustration with the deathliness of her narrative. We have responsibility for working things out differently, not just watching endless repetitions and shaking our heads as overtheres repeat our mistakes for our edutainment. Antigone's claim on us is also in us, about us.

A new retelling, The Story of Antigone, by Ali Smith with illustrations by Laura Paoletti, started me thinking about the nature of Antigone's claim; maybe because it's a telling for younger readers, it both makes the issues of Antigone's claim clear (clearer than a highly academic philosophy book) and allows them to resonate in all their complexities. Smith's Antigone is young – only 12 – the youngest sibling of the family, youngest child of Oedipus. Both her innocence and her experience inform her powerful, internal sense of justice: it's not just because she's a child, seeing in black-and-white, that she decides to bury her brother against the king's orders; nor is it just because of the weight of familial trauma. She figures both with her implacable logic and its courage. She asks a lot of herself.

For Butler, Antigone's claim both legal – a cause of action – and a philosophical critique – a proposition – against Creon's agonistic jurisprudence. More than an argument, a claim can be a right, something staked. Perhaps even more curious, for Butler's interest in performativity and destabilising identity, in internet terminology claims-based identity uses statements made by online entities about themselves or their users as authenticating security tokens. Here, technical concepts of security, identity and authority both meet and play out their political equivalents, like a mini-NSA soap opera:

Claims are not what the subject can and cannot do. They are what the subject is or is not. It is up to the application receiving the incoming claim to map the is/is not claims to the may/may not rules of the application. In traditional systems there is often confusion about the differences and similarities between what a user is/is not and what the user may/may not do. Claims-based identity makes that distinction clear. Once the distinction between what the user is/is not and what the user may/may not do is clarified, it becomes apparent that the authentication of what the user is/is not (the claims) are often better handled by a third party than by any individual application. This third party is called the security token service.Got that? So information technology has literalised Creon's command-control style. Sophocles' play shows what happens when a third party – in this case, the seer Tiresias, who is third-gendered and appears three times in the Theban trilogy – adjudicates what the user may or may not do, based on the service provider's claim about who they are or are not. Tiresias acts as a security token service, telling Creon to save Antigone from a living death, and to bury Polynices with full rights. The tragedy is that this authentication arrives too late: system failure.

|

| Tiresias appears |

In her prose retelling (with rhyming verse choral odes), which retains the mythic Thebes as a setting, Smith uses third person (which drama cannot), and begins in a third-party point of view: that of a crow sitting on the main gate of the city. As in Hans Christian Andersen's weirdest story "The Marsh King's Daughter," there is an affinity between a watchful bird and a troublesome daughter who stands outside the law (there, a stork and a princess who turns into a toad at night). In an appendix in which the Crow interviews her, Smith says her choice of observer comes from the play itself, which is full of references to the crows and dogs who scavenge at the feast of death that is any Greek tragedy, and this one – which starts at the end of a battle – in particular.

For the mother crow, human death is a source of nourishment, and human actions a source of entertainment – just as for the audience in the tragic theatre. Rather than catharsis, however, the mother crow spits up a bolus of food to pass on to her chicks: a story. So the crow – scavenging in death – is the (re)writer as well as the audience: Antigone's claim on her is that her body/story be ingested, taken in, processed, laid claim to. Antigone's death demands that the crow claim her. Antigone (is) in us.

Although the story shifts subtly in and out of being aligned with the mother crow's point of view, it ends with an epilogue, one year after the events of the play, in which she tells the story to her chicks as she feeds them. The call-and-response form in which it is presented, with the chicks demanding

"Tell us the story about: the mad black cloud of crows/the tasty body/the time our own mother sat on the hand of the wise Tiresias/the brave still-alive boy who stood up to his father/the piece of pink material that got woven into our nest"is not only a vivid depiction of how human children engage with storytelling (and a reminder of our adult investment in narrative repetition and its pleasures), but also a model of responsiveness, in which each side of the conversation makes demands on the other, and is heard. This is the opposite of Antigone's negotiation with Creon, in which not only her side of the story, but her narrative structure, is denied by his. Storytelling places teller and listener, Smith's use of form argues, in a relationship of responsibility to each other, conducted via the tropes of the tale.

So displacement could never be enough: the (re)writer/reader needs to take seriously the claim made by the text if she is to act as a security token service, to authenticate the possibility of relationship and of the significant information about life, death and law that flows across it. As well as the dialogic form of the epilogue, the book as a whole creates a dialogue between the text and the illustrations, which shift between full facing-page and embedded in the text. Illustrations are like the family secret of our textual culture: a family member that is ignored. It's there in the work of WJT Mitchell and, in brief, in this thought-provoking discussion of the word/image interaction in children's books by SF Said.

Like the law (unto) itself, the pictures here tell their own version of the story. They tell the reader who does and does not count in the world of the story. Creon only appears once, riding out in pomp: after his declaration against Polynices, he disappears off the side of the page, being represented only by his horse (and finally, when he realises what an idiot he's been, by his horse's arse). The Elders of the Chorus, who are on the side of the status quo, are a faceless flock; instead, there are detailed illustrations of the crow, the dog, a feather, a flower, a piece of pink fabric that links Antigone and Ismene, as well as of the two sisters, Tiresias and Haemon, Creon's son.

|

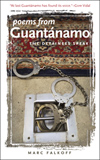

| Bianca Stone, Antigo nick |

The illustrations take a passionate stand for Antigone: they are on her side. Unlike a conventional staging, they make the story only partially visible. The same is true of Bianca Stone's illustrations in Anne Carson's Antigo nick (Sophokles), some of which are printed on slightly opaque translucent mylar, thus revealing/concealing the hand-lettered text beneath. Carson's text is entirely dialogic, using the form of the playscript, and she has performed it live, with a rotating cast (including Judith Butler as Creon!)

Anne Carson: Performing Antigonick from Louisiana Channel on Vimeo.

Carson's retelling is also set in mythical Thebes, and hews far closer to the structure of the play, although it includes anachronistic references to speedboats and Freud. Unlike Smith's chorus of Elders, whose awkwardly-rhymed platitudes are an exercise in comic relief, Carson's Chorus are profoundly poetic, and in some sense the narrator of the play, perhaps in response to Hélène Cixous' essay "Collaborative Theatre," which mourns the loss of the chorus from the post-classical stage, and wonders about the chorus – like Smith's crow's eye view – as a figure for democratic conversation and response-ability.

It is the Chorus who are the interpreters for Carson: figure of both (re)writer and reader/viewer.

WE ARE STANDING IN

THE NICK OF TIME

[ENTER MESSENGER]reads the end of the penultimate choral ode (where the stanza break is actually most of a blank page). It's a painful irony – the Chorus declare victory (Creon has saved Antigone and Haemon in the nick of time) at the moment defeat (oh no, he hasn't) arrives to announce itself. It's easy to think of the Chorus, especially in this moment, as somewhat smug, self-satisfied status quoters – not least as a way of doubly disavowing our own expectations of narrative satisfaction (we feel stupid because we, like the Chorus, want Antigone to survive and she doesn't; and we feel cruel because we really – according to the structural logic in which we have been educated by our culture – want her to die, and she does, and that makes us hate ourselves and feel responsible for her death). But their declaration is a very precise description of the claim made on the spectator: we are standing in / the nick of time.

That is, we are in some sense stand-ins for the historical witnesses (as the Chorus are also our stand-ins on stage); we experience the highlights of the drama, the nicks of time on which the playwright or (re)writer wants us to focus. The sense of 'in'ness coincides with Antigone's claim to be in us: we have to, in another of Butler's phrases, put our bodies on the line, be in the temporality and logic of the play. It could also be read as another kind of claim: can we, as the (offstage) Chorus, stand our bodies in the nick of time? Can we place ourselves between the story as told and its supposedly inevitable ending? Can we look closely at our disavowal in order to change the structural logic and its supposed satisfactions?

The nick of time is an uncomfortable place to be; it is like being in the beak of a crow: sharp, risky. Who would be there? Antigone is the first one to try and place herself therein, between Creon's Law and the law of entropy (time) under which Polynices' body will become the nothing – the lack of a claim-based identity – that Creon wishes it to be. She leaves the city gates in the half-light between night and dawn (a dangerous time for anyone to be about, let alone an unmarried girl traversing a military camp); when caught, she is buried alive, in Creon's casuistical solution to his own law and his own conscience. Time (Death) keeps nicking her, a device that Shakespeare will borrow for the final scenes of both King Lear and Romeo and Juliet.

In Carson's final stand on Antigone's side, Nick becomes a (silent) character, "who continues /////// measuring" at the end of the play (there's that blank-page-gap again). Antigone and Nick share the letters I-N (reversed) in their names; Nick is also the name of Carson's brother, the subject of her work prior to Antigonick, NOX. "in" is one of the final words of Catullus' poem 101, an address to his dead brother, spoken at his grave. The final line of the poem reads "atque in perpetuum, frater, ave atque vale." Carson defines each word of the poem in depth, generally giving (some invented) examples of usage. For "in," she offers only one such, "in noctem death vote," in the exact middle of a long list of relations that "in" can denote.

Those that follow the invented usage could be said to describe Antigone's "death vote," her decision to use the only choice she has to join her brother in death:

in reference to, respecting, with regard to; in proportion to, considering; in comparison with; in accordance with, after, in the style of; so as to become, into; so as to produce or result in; in order to cause, with a view to; in order to make up (a total); for the needs of, for the use against; in expectation of.This is how, as she says of Inger Christensen's masterwork It, prepositions form "all our raw hopes of relation." 'In' is complicated for Antigone: if she is in the city, she cannot be in the family – and moreover, in herself; she learns that with her father's exile and her brother's desecration. Or rather, she stands "in the nick," in the tension or interval of trying to be both: a good citizen and a good sibling; alive and dead; virgin and bride. She stands for the irresolvable, what both is and isn't, may and may not, for what is beyond "claims-based identity." As Smith tells the crow,

through the whole play, the whole story of Antigone, there are questions which, though they are unspoken, are still there nonetheless, about the borders of things… about wildness and tameness… about what is natural and what isn't, what is spiritual and what isn't.

|

| Antigone, Laura Paoletti |

That is to be epi-logos: after the word. There is an after, even to Creon's word, the unbreakable Logos of EuroWestern logocentrism. There's the bird-person who flies off for yet another round of food, for the chicks who will ask for the story again – and gets waylaid interrogating the author, questioning her control of the Logos. Whose point-of-view or appearance makes a nick in the temporal structure of the narrative into/out of which the possibility of change pours.